Burnout

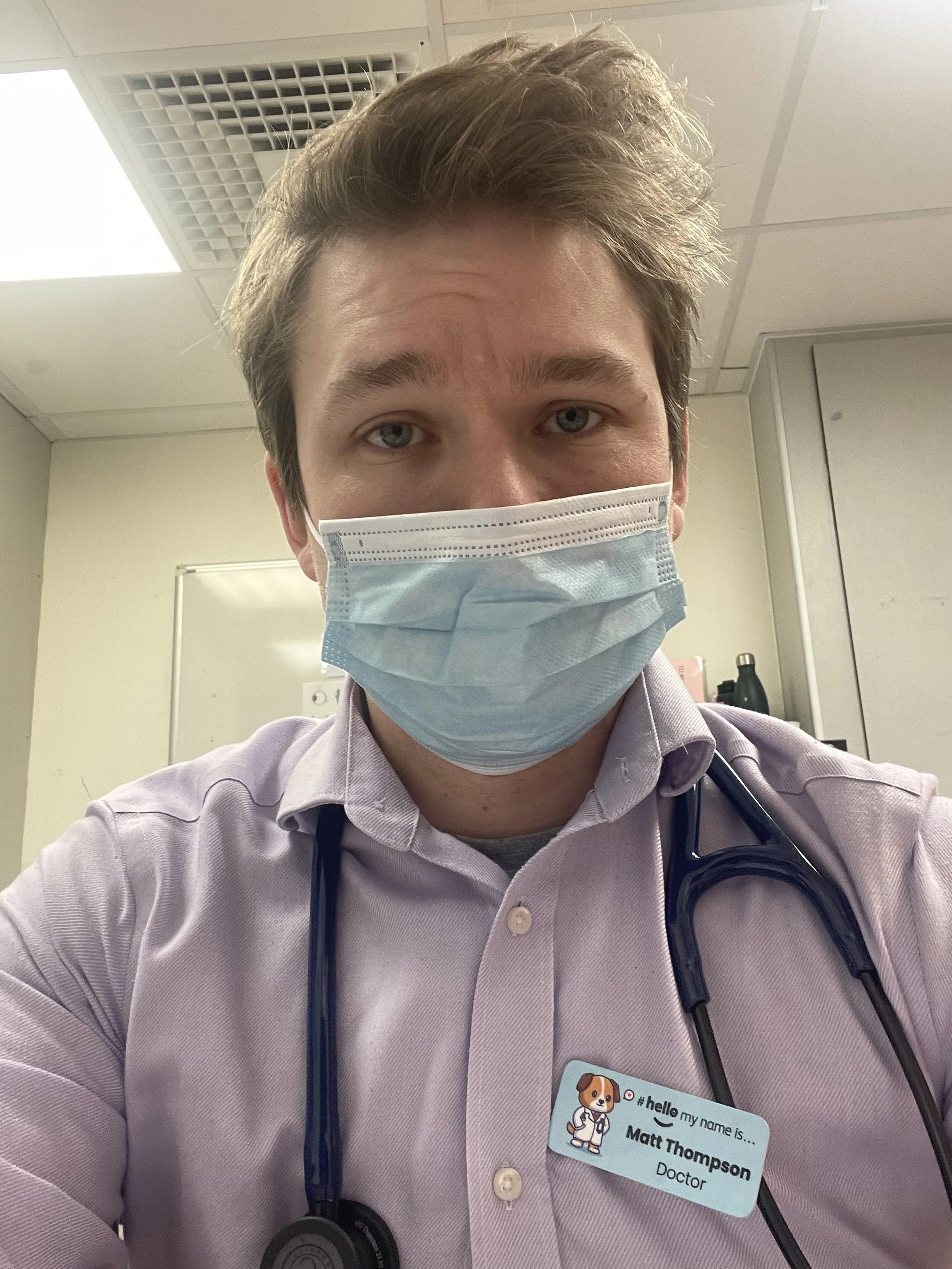

31/12/22 at 06:33 - nearing end of a nightshift

I burned out in my first year as a doctor.

I took time off, increased my antidepressants and signed up for therapy.

Here’s what happened and how I’ve adapted in the nine months since.

Before I began studying medicine in 2018, I was generally a happy-go-lucky, “golden retriever energy” kinda guy. Sometimes it comes out like a childhood accent, but since I began medical school (not forgetting COVID), my mental health has found it hard to adjust to the nature of the sacrifices, inefficiencies and frustrations of healthcare.

Fixing problems was most of my former career. Yet I pivoted from my innovation consulting business to medicine as I grew frustrated at the slow speed of results and the uneasiness of always chasing the next contract. Among other reasons, I wanted faster satisfaction with my fixes and a stable, predictable career. How ironic.

Innovation, efficiency and staff wellbeing are not the NHS’ strong points.

Graduate-entry medical school is not easy at the best of times, with minimal funding for its four-year course (of five year’s worth of content). It was harder when I found I’d forgotten how to study over the last five years, let alone considering the sheer volume of medicine. Receiving a positive HIV needlestick by cleaning a doctor’s tray, and a scalpel cut in a C-section some months later didn’t help the COVID party that was 2020. I started antidepressants for the first time. Medical school was tough.

The start of the Foundation Programme at UHCW went well with my favourite speciality of paediatrics full of lovely patients and supportive colleagues. I found my calling in paediatric emergencies and even developed a whole audit on temperature monitoring around surgery. Rotating after four months is always frustrating, especially after your first FY1 job as you’ve only just become comfortable with the new role and skills of the job.

My next four months were split between Care of the Elderly and acute medicine. I struggled with the ever-changing rota, never staying in one area on a ward longer than a few days across days, nights and weekends. Sadly this was my first experience of a toxic culture too, working with permanent locums and receiving unconstructive & insulting feedback only at the very end.

11/03/23 at 21:09

Out of the frying pan and into the fire. I was glad to leave that behind as I rotated twice the distance away to general surgery at George Eliot Hospital. The team were terrific but we had our work cut out for us. Our days were filled with frustrations with the NHS or local system - some big but many small. These micro-frustrations and the subsequent moral injury kept building. I felt like a zombie lumbering from day to day, swinging from apathy to anger. I hadn’t exercised in weeks…months. A far cry from my normal self. I thought I was just tired and reacting naturally to the environment. Eventually, my colleagues told me they were worried about me. The Postgraduate Support Team encouraged me to take two weeks off.

Somewhere along the way I’d lost faith in the NHS. I never thought that would happen. Someone close to me had been diagnosed late with cancer, months after their valid concerns had been rudely dismissed. I got private health insurance in the hope that I’d never surprise my partner and family with a delayed serious illness.

I was burned out, exhausted and deprived of empathy. I’d lost a lot of myself. I drove to my parents’ home that evening and slept 13 hours straight. I made an appointment with my GP who agreed we increase my sertraline and encouraged me to self-refer to NHS Practitioner Health. I’d never heard of them, but now I tell everyone about them.

I was put in touch with the most amazing GP who I am still in regular contact with. My thoughts were nothing new to her, although slightly more exaggerated due to my previous career. She expertly informed me that “you don’t recover from burnout in two weeks”. I needed six weeks minimum. This terrified me as I’d long been adamant I didn’t want to make my training any longer than it needed to be. Once I’d informed everyone I needed to and been assured by my colleagues that they would be fine without me, my discomfort began to settle.

That’s one thing holding many healthcare professionals back from looking after themselves - the fear, shame or guilt of leaving your short-staffed colleagues with even less. We already give so much of ourselves to this job. Try not to give your health.

Another fantastic benefit of NHS Practitioner Health was the included Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). I’d applied through IAPT for some during medical school, but my unpredictable schedule made booking difficult. Now I’ve had regular sessions, I must admit it hasn’t been revolutionary but has helped me recognise when I’m getting in my way.

Black & white thinking, mental filter, jumping to conclusions and catastrophising are the traits I struggle with. Recognising these in the moment, or at least in reflection, has helped me in my recovery.

During these six weeks, I avoided anything that reminded me of medicine. Not even TV shows or podcasts I had once enjoyed. I started studying Spanish and Python programming (didn’t last long) in the hope I could gain skills for a new career. I finally began exercising again. Emily and I went to the zoo. Meditating with Headspace didn’t work for me, but a new garden hammock under the summer sun did.

The six weeks were just the start. My anxiety grew as my return to work drew closer, so much so that I abandoned a small B&B getaway with the family to be alone. I despised ward work, the pressure of on-calls and long hours. We upped my sertraline again as I began my final two weeks of general surgery. The light at the end of the tunnel helped.

Since I wrote the above in February 2024 and promptly forgot about it, I’ve been diagnosed with ADHD. No surprises there.

A lot has happened since, a few positives but many more frustrations, particularly with the NHS and its awful beaurocracy & workforce dehumanisation. But that’s for another blog soon… if I ever get around to writing it.